PAULINE ANAMAN SENIOR POLICY ANALYST

AFRICA CENTRE FOR ENERGY POLICY (ACEP) AVENUE D., HSE NO. 119, NORTH LEGON ACCRA

AND JOHN DARKO

GHANA INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION (GIMPA) FACULTY OF LAW

P.O BOX AH 50-ACHIMOTA-ACCRA

Abstract

It came into force in 2011, a year after the commercial production of oil began in Ghana. For all the advocates of oil revenue management legislation, the Petroleum Revenue Management Act (PRMA), 2011 (Act 815) could not have come at a better time. It held the key to avoiding the resource curse phenomenon. Its implementation will make Ghana perhaps one of the few resource rich nations to put the “demon” of resource curse behind it and lead it to the path of success. Having gone through its first amendment in 2015, this paper sought to analyse the implementation realities of the PRMA for whether the PRMA has been an effective tool for public investment and consumption smoothing. The key finding is that after 8 years of petroleum revenue receipts, there is not much to show that revenues have been invested to achieve development priorities. Discretionary powers of the Minister to select priority areas for Annual Budget Funding Amount (ABFA) investment, and to cap the Ghana Stabilization Fund (GSF) remain the Achilles heel of achieving the objectives of the ABFA and the GSF. Section 24(1) of the PRMA also creates severe accountability loopholes that risk intentional diversion of unutilized ABFA for other purposes through a joint operation between that provision and sections 26 and 49 of the Public Financial Management Act, 2016 (Act 921).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ABFA Annual Budget Funding Amount

AOE Additional Oil Entitlement

BR Benchmark Revenue

CAPI Carried and Participating Interest

GHF Ghana Heritage Fund

GIIF Ghana Infrastructure Investment Fund

GNPC Ghana National Petroleum Corporation

GPF Ghana Petroleum Funds

GRA Ghana Revenue Authority

GSF Ghana Stabilization Fund

LTO Large Taxpayer Office

MoF Ministry of Finance

NAPR Net Actual Petroleum Revenue

PFMA Public Financial Management Act

PHF Petroleum Holding Fund

PIE Public Investment Expenditure

PR Petroleum Revenue

LIST OF CASE LAW

Dodzie Sabbah v The Republic

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: The PRMA’s framework for petroleum revenue collection and distribution

Figure 2: Ghana’s annual petroleum receipts (US$) from 2011 – 2017

Figure 3: Petroleum revenue disbursement from the PHF (2011-2017)

Figure 4: ABFA utilization framework under the amended PRMA

Figure 5: Disbursement architecture of the Ghana Stabilization Fund

LIST OF STATUTES

Ghana Petroleum Corporation Act, 1983 (PNDC Law 64)

Petroleum Revenue Management (Amendment) Act, 2015 (Act 893) Petroleum Revenue Management Act, 2011 (Act 919)

Public Financial Management Act, 2016 (Act 921) The 1992 Constitution of Ghana

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Fiscal contribution of the Mining Sector to Domestic Revenue Mobilization in Ghana (2011-2017)

Table 2: Public investment expenditure decisions in ABFA utilization

Preface

When we set out to write on Ghana’s Petroleum Revenue Management Act, several areas of concern came to mind. However, we settled on the above topic to assess the PRMA and to determine whether its bid to ensure efficient expenditure of the revenue from the oil has been achieved or at least can be achieved given all the indices of an effective PRMA.

Having existed for nearly seven (7) years now, and amended in 2015,1 the time is ripe for a review of the implementation realities of the PRMA in light of the PRMA provisions. This paper thus analyses the loopholes in Ghana’s Petroleum Revenue Management Act (PRMA) as regards the Annual Budget Funding Amount (ABFA) and the Ghana Petroleum Funds (GPF) and juxtaposes these against implementation realities to highlight public financial management challenges, if any. It also makes recommendations that can make the law more responsive to public financial management principles in order to achieve the PRMA objectives on public investment and consumption smoothing.

The sources of information, in addition to the PRMA, are secondary in nature. They include the Hansard on the PRMA, annual and reconciliation reports by Ghana’s Ministry of Finance, national budgets, reports by civil society organizations and think tanks, articles, media reports, and legal documents.

This paper is divided into three (3) parts. Part one discusses the policy behind Ghana’s Petroleum Revenue Management Act whilst part two (2) tackles the Public Financial Management features of Ghana’s Petroleum Revenue Management Act. In the final part, we analyse the PRMA and its implementation in light of public investments and consumption smoothing.

PART ONE

Public financial management: the policy behind Ghana’s Petroleum Revenue Management Act

- The role of public financial management in averting the resource curse

Revenues from extractive resources such as minerals and petroleum are public finances that ought to be prudently managed for three major reasons. First, the resource is generally owned by the people of host countries to whom maximum benefits from extracting the resource must accrue. It is only fair that meaningful investments are made to benefit the beneficial owners of the resources. Second, because extractive resources are finite and commodity prices are volatile, revenues must be properly invested in ways that sustain the host country during boom and bust times, as well as when the resource is depleted. Thirdly, the various stages along the extractive sector decision chain are susceptible to corruption and rent-seeking. This is because the resource is “free” and citizens tend to be less vigilant. Putting in place effective public financial management systems can go a long way to increase transparency and accountability in resource revenue use and investment. Countries such as Norway, Chile, and Tanzania have had their economies and wellbeing of citizens transformed due to effective management of the temporary public resource.

There are however country examples of how poor management of extractive resource revenues, resulting from weak legal and institutional governance arrangements, reinforces economic downturn, poverty, and poor human development. Nigeria is a classic example. Between 2011 and 2015, Nigeria forfeited $1.5 billion in petroleum revenues due to corruption in petroleum contract award processes.2 This lump sum, if saved at an interest-free rate and holding everything else constant, could have fully funded the capital expenditure component of Nigeria’s education budget as well as total budgeted expenditure on health for the 2017 fiscal year.3 In Sierra Leone, the presence of, and revenues from, diamond resources partly fuelled the country’s civil war from the 1990s to 2002.4 Brazil, another country rich in oil, iron ore, coffee and soybeans, struggles to eliminate its vast and dangerous slums.5

- Weak public financial management practices in Ghana’s mining sector: lessons for the petroleum sector

Oftentimes, when Ghanaians engage in the discussion about the development implications of weak resource revenue management, they look beyond the shores of Ghana. But a look at Ghana’s own mining sector suggests that the country is no exception to the resource curse menace. Ghana has been extracting solid minerals for over a Century. However, the mining sector is still considered as a curse to the country due to its deleterious environmental effect on the country, even though the sector has contributed immense revenue to the nation’s kitty.6 The table below shows the mining industry’s contribution to domestic revenue in Ghana from 2011 to 2017.7

Table 1: Fiscal contribution of the Mining Sector to Domestic Revenue Mobilization in Ghana (2011-2017)

| YEAR | TOTAL MINING CONTRIBUTION TO GRA (GHȻ) | % MINING TO TOTAL DIRECT REVENUE |

| 2011 | 1,034,221,712 | 28% |

| 2012 | 1,461,202,977 | 21% |

| 2013 | 1,104,047,315 | 19% |

| 2014 | 1,238,634,779 | 16% |

| 2015 | 1,354,379,971.47 | 15% |

| 2016 | 1,650,000,000 | 16% |

| 2017 | 2,160,000,0008 | 16.30% |

Between 2011 and 2017, the mining industry contributed a little over GHC10 billion to the national coffers. This approximately represents, on average, 19% of total domestic revenue that was mobilized by the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA) each year. But in the absence of a mineral revenue management law, the GHC10 billion revenue, together with significant receipts from preceding years, have vanished into thin air upon hitting the consolidated fund. No public asset in the country can be described as having been financed with revenues from minerals. Instead, the sector is widely known for its devastating impacts on the environment and socio-economic wellbeing of people in mining communities.

It is against this backdrop that, following the discovery of commercial oil in Ghana in 2007, there was unanimity across the political divide to fashion out institutions and laws that would effectively manage the resource and steer the country away from becoming oil-cursed. After intense public debates and civil society consultations, the Petroleum Revenue Management Act (PRMA) was passed in 2011,9 with the underlying public financial management principle to “provide the framework for collection, allocation, and management of petroleum revenue in a responsible, transparent, accountable and sustainable manner for the benefit of the citizens in accordance with article 36 of the constitution and for related matters”.10 Indeed, prudent management and investment of extractive revenues for sustainable development is a key aspect of the extractive sector decision chain11 that can reverse or prevent the resource curse in resource-rich developing countries.

PART TWO

Public Financial Management features of Ghana’s Petroleum Revenue Management Act Generally the management of public finance in Ghana is governed by the Public Financial Management Act, 2016, (Act 921). The object of the Act is to “regulate the financial management of the public sector within a macroeconomic and fiscal framework”12. The features of the PRMA will therefore be looked at in the light of act 921. In line with fiscal policy principles and objectives of Act 921 such as prudent management of natural resources for the welfare of current and future generations, fiscal sustainability, and transparency, Petroleum Revenue Management (Amendment) Act of Ghana prescribes rules for how revenues should be disbursed and used. It also prescribes the roles of institutions in collecting, distributing, investing, and accounting for petroleum revenues. This part discusses these into details.

- The architecture of petroleum revenue receipts and disbursement under the PRMA

As a public financial management tool, the PRMA is clear about the sources of petroleum revenues, the central fund to which these revenues should be deposited, the distribution formula to various funds from the central fund, and the purpose of each fund. This has been summarized in the infographic below:

Figure 1: The PRMA’s framework for petroleum revenue collection and distribution

Source: ACEP, 201813

The Petroleum Holding Fund is the central recipient of petroleum revenues from various sources.14 In order of priority, the National Oil Company (NOC), presently the Ghana National Petroleum Corporation (GNPC), is the first in line to receive revenues from the PHF. Next are the national budget through the Annual Budget Funding Amount (ABFA), the Ghana Petroleum Fund, and other exceptional purposes, in that order.15

- Payment to the National Oil Company (NOC).

The National Oil Company (NOC) in Ghana is the Ghana National Petroleum Corporation (GNPC). The GNPC was established in 1983 to undertake the exploration, development, production and disposal of petroleum.16 GNPC is at all times party to petroleum agreements between the Republic of Ghana and a contractor. As such, it holds an initial participating carried interest of at least fifteen percent (15%) on behalf of the State, and has an option after commercial discovery to take additional participating interest as determined in the petroleum agreement. The additional interest is a paid up interest in respect of cost incurred in the conduct of petroleum activities aside exploration costs.17

For participating in the petroleum business, GNPC is entitled to receive its equity financing costs from revenues due from the carried and participating interests (CAPI) it holds for the state. It is also entitled to receive not more than 55% of the net CAPI18 for purposes not clearly stated in the PRMA, although it may be inferred to finance the Corporation’s general operations.

Disbursement from the PHF to GNPC is consistent with section 16(1) of PNDC Law 64 which provides that “the Government may from time to time approve advances and grants to the Corporation out of money provided by the Government for that purpose.” GNPC will however cease to receive its share of the net carried and participating interest from the government, although it may continue to receive monies for its equity financing cost from the CAPI until depletion of Ghana’s petroleum reserves.19

- Payment to the Annual Budget Funding Amount (ABFA)

“Annual Budget Funding Amount” means the amount of petroleum revenue allocated for spending in the current financial year budget.’20 When GNPC’s share of petroleum revenue is disbursed, the remaining amount (net actual petroleum revenue) may be more or less of the Benchmark Revenue (BR). The BR is “the estimated revenue from petroleum operations expected by the Government for the corresponding fiscal year.”21 The ABFA receives an amount from the PHF that is equal to or less than 70% of the BR if the net actual petroleum revenue (NAPR) is more than the BR.22 On the other hand, if the NAPR is less than the BR, not more than 70% of that NAPR is disbursed to the ABFA.23

The ABFA is expected to be utilized in ways that result in maximizing the rate of economic development, promoting equality of opportunity with a view to ensure the well-being of citizens, and undertaking even and balanced development of the regions.24

- Payment to the Ghana Petroleum Fund (GPF)

The Ghana Petroleum Fund (GPF) is the combined fund of the Ghana Heritage Fund (GHF) and the Ghana Stabilization Fund (GSF).25 “The purpose of the GHF is to provide an endowment to support development for future generations when petroleum reserves have been depleted.”26 With the awareness of the risk of revenue volatility from the petroleum resources, the GSF was established as a savings fund with the object to smoothen the country’s consumption in times of unanticipated petroleum revenue shortfall.27

When net actual petroleum revenue (NAPR) is more than the Benchmark Revenue (BR), the GPF receives the excess revenue. In addition to this, not less than thirty percent (30%) of the BR is transferred to the GPF. Where BR is equal to the NAPR, the GPF receives no excess petroleum revenue and the basis for calculating transfers to the GPF is the BR. However, the GPF takes not less than 30% of the NAPR in the event that NAPR is less than the BR. Monies to the GPF are essentially the amount remaining after the ABFA has been disbursed. Further disbursement is made from the GPF to the GHF and GSF in that order of priority. The GHF receives not less than 30% of funds in the GPF. The remainder goes to the GSF.28

- Payment for exceptional purposes

This fourth line of petroleum revenue transfer from the PHF exists for three main purposes as stated in section 24 of the PRMA: tax refund and payment of management fees; payment of royalties for on-shore operations; and payment of compensation to communities adversely affected by petroleum operations. These provisions were informed by the well documented impact of oil exploration activities on host communities,29 and the likelihood that on-shore petroleum exploitation may begin in the Voltaian Basin upon successful commercial find.

- Public financial management role(s) of various actors in Ghana’s petroleum revenue governance space

The PRMA affects the collection, allocation, and management by government of petroleum revenues derived from upstream and midstream petroleum operations.30 Various institutions perform different but complementary roles in ensuring that the provisions of the PRMA are effectively implemented to achieve expected outcomes. This part of the paper thus identifies these institutions and discusses, in a normative form, their roles in light of the scope of application of the PRMA.

- Roles of institutions in revenue mobilization and operational management of the PHF

- Revenue paying entities

State and non-state entities who undertake upstream and midstream petroleum activities within Ghana’s territories have contractual and legal obligations to make certain payments to the State. The payments constitute revenues to the State and include royalties, additional oil entitlement (AOE) surface rentals, receipts from petroleum operations, sale, or export, corporate income tax, and any other payments. By the 15th day of each ensuing month, the payment entities are required to make direct payment into the Petroleum Holding Fund (PHF) of all amounts assessed as due to the State in any particular month.31 To illustrate, surface rentals assessed as due to the State in the month of June of any particular year must be paid directly into the PHF by the payment entity before or on 15th July of the year in question. Once payment is made into the PHF, the entity must notify the Ghana Revenue Authority in writing.32 Any defaulting paying entity shall be charged a daily penalty of at least 5% of the original amount due.33

- Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA)

The Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA) is mandated with a three-pronged role to assess, collect, and account for petroleum revenues due the state. This appears to be the primary responsibility of the domestic tax revenue division, particularly the Large Taxpayer Office (LTO), for two reasons. First, its core functions include identifying tax payers, assessing the tax payer to levies and taxes, collecting taxes and levies, and paying all amounts collected into the consolidated fund.34 Secondly, oil and gas companies fall within the list of LTO companies.35 Assessment involves all valuations and evaluations regarding a payment entity’s tax and other liabilities which constitute sources of petroleum revenues to the State. The GRA is mandated to follow principles set out in the Public Financial Management Act, 2016 (Act 921) “to ensure sufficient revenue mobilisation to finance Government programmes”36

It is however not clear how the GRA performs its petroleum revenue collection roles. This is based on two reasons; first, the GRA generally pays taxes and levies collected into the consolidated fund.37 However, petroleum revenues are required to be paid directly into the PHF.38 Secondly, the PRMA requires the paying entity to directly make payments due the State to the PHF. Accounting for the revenues may include verifying, keeping records, and publicly publishing all payments made directly to the PHF by the payment entities. For example, the GRA is required to report and record as payment to the PHF the dollar equivalent of payments to government in petroleum (barrels).39

- Bank of Ghana

The Bank of Ghana (BoG) hosts the Petroleum Holding Fund (PHF); the fund to which petroleum revenue from all sources is deposited. The record of all receipts of petroleum revenue are kept by the BoG. The PRMA provides that subsequent transfers would be made from the PHF in accordance with the provisions of the Act. It stands therefore to reason that BoG, being the host of the PHF, is responsible for disbursing monies from the fund to the GNPC, ABFA, GPF (comprising of the GSF and GHF) and any other fund for exceptional purposes.40 The BoG also ensures transparency and accountability of petroleum receipts by providing the Minister of Finance with accurate records for publication. Even though the BOG is not specifically fixed with a responsibility in exercising their powers under the PFMA, one can infer that so long as it is the host of PHF and responsible for disbursing funds to GNPC etc, it is subject to the PFMA.41

- Parliament of Ghana

The Parliament of Ghana decides the percentage of petroleum revenue that should be transferred into the Ghana Heritage Funds (GHF).42 Despite the restrictions on transfer of revenue from the GHF, Parliament has the power under the PRMA to, from time to time and by resolution through two-thirds majority votes, review such restrictions and authorize transfer of interest accrued on the GHF to any other fund established under the PRMA.43 Review of restriction is for every fifteen years beginning after 2011 when the PRMA was passed. Thus, in 2026, 2041, 2056 and every fifteenth year thereafter, Parliament can order transfer of petroleum revenue from the GHF. Also, as part of its oversight role of the national budgetary process, the Parliament of Ghana approves allocation to and expenditure from the Annual Budget Funding Amount. Parliament is also responsible for approval of a long-term development plan to guide the investment of the ABFA.

A look at section 13 of the PFMA and PRMA show that Parliament is performing its financial management responsibility.

- Roles of institutions in the use and oversight of petroleum revenue

- The National Development Planning Commission (NDPC)

Although not specifically mentioned in the PRMA, the NDPC has a significant role to play in the management of Ghana’s petroleum revenue. The PRMA envisages a long term development plan to guide petroleum revenue investment in order to achieve the objectives of the ABFA to maximize the rate of economic development, promote equality of opportunity in a view to ensure the well- being of citizens, and undertake even and balanced development of the regions. These PRMA provisions tie in with the NDPC’s development planning mandate under article 87(2) of the 1992 Constitution, including:

‘… [S]trategic analysis of macro-economic and social reform options…; development of multi-year rolling plans taking into consideration the resource potential and comparative advantage of the different districts of Ghana; …proposals for ensuring the even development of the districts of Ghana by effective utilization of available resources; [and] monitor, evaluate and co-ordinate development policies, programmes and projects.’

From its functions as gleaned from article 87 of the Constitution, 1992, the NDPC is supposed to be one of the institutions which will ensure responsible financial management in the country

- The Ministry of Finance

The Ministry of Finance, headed by the Minister of Finance, is responsible for the may make regulations on the PRMA regarding pricing, petroleum metering, and operational management and guidelines for the management of the Petroleum Funds.44 The Ministry of Finance has the responsibility for the overall management of the funds45. Indeed, it is the Ministry’s responsibility under the PFMA to ensure that all expenditures are done in accordance with public financial management principles.46

- Investment Advisory Committee

The responsibility of the Investment Advisory Committee is to formulate and propose to the minister the investment options available for the petroleum funds.47

- Public Interest and Accountability Committee (PIAC)

One of the most important institutions that ensures transparency and accountability in the management of Ghana’s petroleum revenues is the Public Interest Accountability Committee (PIAC). The Committee is an independent oversight body that ensures that the provisions of the PRMA regarding the use and management of petroleum revenues are complied with at all times by all stakeholders. It also has a duty to provide the platform for public debate to ensure that the

public is informed about, and involved in, how the funds are used in accordance with development priorities of the country. By conducting independent assessment on the management and use of petroleum revenues, PIAC provides an important oversight role of the legislative and the executive arms of government. PIAC is required under the PRMA to present semi-annual and annual reports to Parliament and the Presidency. Although the scope of the report is not defined, it can be reasonably inferred to speak to progress made in achieving PFMA, PRMA and PIAC objectives every year.

- Audit Service

The auditor general is also required to audit the petroleum fund accounts after every financial year and submit its report to parliament and publish same after one month of the submission to parliament.48 Indeed, Audit is at the heart of the public financial management. Sections 83 to 88 of the PFMA are dedicated to audit of the covered entities.

- Civil Society Organizations

Section 49(7) of the PRMA makes it clear which institutions have responsibility to ensure transparency and accountability in the management of oil revenue. These include the Minister of Finance, Parliament, and PIAC.49 But modern day fight for transparency and accountability cannot be left to governmental institutions. Even more than the state institutions, CSOs like ACEP, IMANI, CDD, and Occupy Ghana have been at the forefront for the fight for transparency and accountability in resource governance in Ghana.

- Citizenry

The PRMA requires citizens to take active part in the management of the oil revenue. Thus the Act requires PIAC under section 52(b) to provide platform for public debate about whether spending prospects, use and management of the ABFA conform with development priorities. An enlightened citizenry is a national asset in driving effective management of petroleum revenues to achieve development goals.

In theory, the PRMA is in consonance with good governance principles of public financial management of Act 921 in ensuring transparency and accountability in petroleum revenue receipts, disbursement, and investment that could have transformative effects on the welfare of the people of Ghana.

PART THREE

Implementation realities of the PRMA in light of public investments and consumption smoothing

- Ghana’s petroleum revenue receipts and disbursement in practice (2011 to 2017)

By the end of 2017, the Petroleum Holding Fund (PHF) had received about US$ 4.01 billion (over GHC 10 billion) as revenues from various sources. The annual breakdown of receipts is presented in the figure below:

Figure 2: Ghana’s annual petroleum receipts (US$) from 2011 – 2017

Source: Ministry of Finance, 2016 and 2017

The size of petroleum revenue is a function of barrels of oil produced and price. The persistent rise in petroleum revenue from 2011 to 2014 was the result of stable production in-country and increasing petroleum price on the global market. But from 2015, the average annual price of petroleum dropped significantly to less than $50 per barrel from about $103 per barrel from the previous year. Fallen crude prices, coupled with production shortfalls from the Jubilee field arising from frequent shut down of the FPSO Kwame Nkrumah due to turret bearing challenges, led to shortfalls in petroleum receipts between 2015 and 2017 compared to the trend in revenue growth from the preceding years. The pattern of Ghana’s petroleum receipts speaks to the volatility of resource revenues and the need to invest this temporal revenue wisely to achieve measurable and meaningful development as envisioned by the drafters of the PRMA.

Data from Ghana’s Ministry of Finance show that between 2011 and 2017, the ABFA received the highest aggregate sum from the PHF to the tune of US$ 1.64 billion (41%), compared to the GPF (28%), and GNPC (31%). Details of the breakdown are presented in the figure below:

Figure 3: Petroleum revenue disbursement from the PHF (2011-2017)

Source: Ministry of Finance, 2016 and 201750

A critical analysis of the year-on-year disbursement of revenues from the PHF shows that the Ministry of Finance followed the PRMA formula. Monies disbursed to the GNPC have consistently been less than 55% of the net CAPI. The ABFA has consistently been exactly 70% of the net actual petroleum revenue and the remaining 30% disbursed into the GPF. The GSF and GHF component of the GPF also respectively received $776.55 million and $323.72 million, representing 70.6% and 29.4% respectively of the GPF amount in accordance with section 11(3) of the PRMA (as amended). In 2017, about $12.44 million received from corporate tax, surface rental, and interest on the PHF was not disbursed from the PHF due to the time of receipt. 51

Amidst the revenue volatility challenge, and in spite of meeting disbursement requirements, industry players are of the view that the use of petroleum revenue has achieved little meaningful impacts over the years for current and future generations. The ensuing parts of this paper explores whether this assertion is a question of law or a shirk of government’s responsibilities or both.

- The Annual Budget Funding Amount (ABFA) investment for sustainable development

To achieve sustainable development, the PRMA is clear about the specific objectives of government’s investment of the ABFA: increased economic development, improved wellbeing of Ghanaians through the creation of equal economic opportunities, and even and balanced development of the geographical regions.52 The achievement of these objectives are anchored on public financial management principles of efficient allocation, responsible use, and effective monitoring of the ABFA expenditure.53 Despite these good intentions, certain provisions of the PRMA make the law a self-defeating one by creating room for actors to take decisions that minimize the good intentions of the law. Three of such are discussed below:

- Discretionary powers in the selection of priority areas and implications for efficient ABFA utilization

In his book, “Interpretations of legal history”, Roscoe Pound points out the need for law to be flexibly stable in order to secure its sanctity of purpose in the face of changing societal circumstances.54 It goes therefore to say that a good balance of flexibility and stability is required to achieve the intended purpose(s) of law. In this discussion, we show how flexibility of the PRMA without appropriate regulations has resulted in abuse of discretionary powers to derail ABFA investment objectives.

According to section 21(2) of the PRMA, ABFA expenditure ought to be made in accordance with a medium term expenditure framework that is consistent with an approved national development plan.55 In spite of this rigid provision, the drafters of the PRMA introduced some flexibility to ensure that even in the absence of a national development plan, the principles of public financial management in the PRMA would be implemented to achieve the intended objectives of the ABFA.

Section 21(3) provides thus

“Where the long-term national development plan approved by Parliament is not in place, the spending of petroleum revenue within the budget shall give priority to, but not limited to, programmes and activities relating to:

- Agriculture and industryPhysical infrastructure and service e delivery in education, science, and technologyPotable water delivery and sanitationInfrastructure delivery in telecommunication, road, rail and portPhysical infrastructure and service e delivery in healthHousing deliveryEnvironmental protection, sustainable utilization, and protection of natural resourcesRural development

Developing alternative energy sourcesStrengthening of institutions of government concerned with governance and maintenance of law and orderPublic safety and securityProvision of social welfare and protection of the physically handicapped and disadvantaged citizens.”

The phrase “…not limited to…”, as used in relation to the priority areas suggests that the list of areas is non exhaustive. To deepen the gains from the use of the ABFA, the PRMA shrinks the scope of ABFA investment by granting discretionary powers to the Minister under section 21(5) to select at most four priority areas specified in section 21(3) at a 3-year interval.56 The effect of the combined operation of subsections 3 and 5 of section 21 is that the Minister is at liberty to couch new areas that are outside the specifics of the law.

In practise Ghana has not had a long term national development plan to guide investment of the ABFA ever since the PRMA became effective in 2011. In enforcing section 21(3) and (5) of the PRMA, the Minister of Finance has indeed couched priority areas that fall outside the list in section 21(3). For example, the priority areas selected for ABFA investment between 2011 and 2016, were

- Expenditure and amortization of loans for oil and gas infrastructure

- Roads and other infrastructure

- Agriculture modernization and

- Capacity building.

Agriculture modernization is the only priority area that matched the requirements of section 21(3) of the PRMA. A careful interrogation of specific programmes and activities under capacity building, and roads and other infrastructure priority areas reveals that ABFA was invested in ways that exceeded the limit of 4 priority areas as imposed by the law. For example, in 2015 alone, ABFA expenditure under the roads and other infrastructure priority area was on capital projects in the following five (5) areas listed in section 21(3) of the PRMA: roads and highways, energy, water, health, and education. Beyond these were expenditure on transport and transfers to the Ghana Infrastructure Investment Fund. Funds disbursed for capacity building were also spent on goods and services in education. These, together with the priority areas of agriculture modernization and amortization of loans brought the priority areas of ABFA investments to nine in 2015 alone.57

This was the nature of ABFA investment until 2017, when the new government re-organized the priority areas to meet the demands of the law. For the 2017 to 2019 investment phase, ABFA will be expended on ‘…agriculture, physical infrastructure and service delivery in education, physical infrastructure and service delivery in health, and road, rail, and other critical infrastructure development.’58 However, by the nature of its couching, the road, rail and other critical infrastructure development priority area leaves room for abuse, similar to the reality in preceding years.

Although it is reported that the medium term development plan informs the selection of priority areas,59 the procedures for the selection of priority areas under the discretion of the Minister remains unclear in the minds of the public. This is because, there are no regulations to govern the exercise of such discretionary powers contrary to the 1992 Constitution’s directives on the exercise of discretionary power. Article 296 (c) of the 1992 Constitution provides that:

‘Where in this Constitution or in any other law discretionary power is vested in any person or authority-… where the person or authority is not a judge or other judicial officer, there shall be published by constitutional instrument or statutory instrument, regulations that are not inconsistent with the provisions of this constitution or that other law to govern the exercise of the discretionary power.”60

It has already been established that the PRMA clothes Ghana’s Minister of Finance with wide discretionary powers. But the Minister of Finance’s office does not fit the category of persons exempted from requiring regulations to exercise discretionary powers; i.e. judges or judicial officers. It is for this reason that the PRMA provides also for the making of regulations on the operational management and guidelines for the management of petroleum funds. Section 60(1) and (2)c provides that

“The Minister may by legislative instrument make Regulations for the effective performance of this Act. The regulations made by the Minister shall include operational and management guidelines for the management of the Petroleum Funds.”

It has been established in Ghanaian case law that the use of the words “shall” and “may” mean differently. While the former imposes a mandatory requirement to act or not act, the latter is discretionary. In the case of Dodzie Sabbah V. The Republic61 the Supreme Court reiterated the position that “shall” is mandatory while “may” is discretionary.

The reasonable conclusion we draw from juxtaposing case law principles against the constitutional and PRMA provisions is that, while it is constitutionally mandatory for regulations to be enacted to guide the Minister of Finance’s exercise of discretionary powers, the PRMA makes it

discretionary for the Minister to make regulations for the effective performance of the Act. However, where the Minister decides to make such regulations, it becomes mandatory to make one that affects the management of the Petroleum Funds. The incongruence of the law is exposed by the operationalization of the PRMA for 7 years now without any regulation, resulting in further infractions of the PRMA. The minister is therefore exercising discretionary powers without regulations in flagrant violations of the constitution.

Linked to the challenge of selecting priority areas in the absence of regulations is the issue of thin spread of ABFA investment on many programmes and activities. In 2013 the government of Ghana financed 229 projects with ABFA of GHC543.8 million.62 This was reduced in 2014 to 179 projects under five priority areas following strong advocacy against thin spread of ABFA by civil society groups. At the time, ABFA utilized was about the same size (GHC549.4 million) as that in 2013.63 In 2015, ABFA disbursement to education as a share of total ABFA was 16.7%. Yet, about 53% of all projects funded by the ABFA (about 172 of them) was related to infrastructure and goods and services delivery in education.64 As a result of thin spread of ABFA on many projects, no single capital project has been executed solely with the ABFA. ABFA is co-mingled with other funds such that projects, whether new or under rehabilitation, are not completed on time to serve intended beneficiaries. Some projects have stalled due to delay in release of counterpart fund, leading to cost overruns.65 In certain instances, ABFA is used to finance interest accrued as a result of late payments to contractors. This practice is unsustainable because it reinforces existing inefficiencies in project finance. Moreover, not all ABFA-funded investments can be effectively monitored for learning to deepen impacts. There is therefore the need for the Ministry of Finance to collaborate strongly with local governments, and Ministries, Departments, and Agencies (MDAs) to undertake planned ABFA investments. There is also the need to decentralize funds to cut down on bureaucracies that affect timely release of funds to contractors.

- ABFA for public investment expenditure and possible accountability loopholes

The PRMA as amended provides that not less than 70% of the ABFA should be used for public investment expenditure in accordance with development plan and with section 21(3) and (5). Out of this, up to 25% should be transferred to the Ghana Infrastructure Investment Fund (GIIF) for the purpose of infrastructure development (figure 5).66 Section 57(1) and (3) also charges the annual programmed budget of the Public Interest and Accountability Committee (PIAC) on the annual ABFA. The infographic below demonstrates how the ABFA is disbursed in accordance with the law.

Figure 4: ABFA utilization framework under the amended PRMA

Source: ACEP, 2018

The above directive raises the following questions:

- What constitutes public investment expenditure?

- What happens to the balance of ABFA in circumstances where not all of ABFA is invested in public investment expenditure? Does the amendment of the Act allow for PIAC’s financing from the ABFA make PIAC a priority area for ABFA investment under section 21(3) of the Act?

The law and practise of ABFA utilization for public investment expenditures before and after the 2015 amendment of the PRMA have been analysed in this part to bring to light how contentions in the law has impacted on the use and objectives of the ABFA. To aid proper interpretation of the law, we have referenced the Parliamentary Hansard on the PRMA, and our professional experiences of constant engagement on the issue with key stakeholders in Ghana’s petroleum sector.

- What constitutes public investment expenditure?

Instinctively, investment expenditure connotes putting [financial] resources in those things that have productive lifespan over several years. That investment expenditure should lead to capital formation has influenced budgetary classification of capital outlay by government as public investment. Physical infrastructure such as roads, telecommunication infrastructure and sanitation networks would immediately be classified as such.67 But the scope of public investment expenditure extends beyond physical infrastructure. According to UNCTAD, investment in human

capital development through government current spending on health and education, as well as maintenance of physical assets, could yield benefits that span a lifetime.68 This assertion is also supported by the IMF and some economists who have suggested that countries that suffer from a scarcity of human capital could benefit greatly from investments in education and health,69 albeit current. The most important factor to consider in public investment decisions, be they capital or current, is their pay-off ability. Public investment expenditures should be able to support growth over a longer term. 70 Until it was amended in 2015, Ghana’s PRMA did not define what should constitute public investment expenditure (PIE) to which a minimum of 70% of ABFA shall apply, although the listed priority areas in section 21(3) suggested that PIE could encompass both capital and current expenditures. ABFA utilization for the period before 2015 covered both capital expenditure and expenditure in goods and services under the chosen priority areas. The current position of the law, following amendment, is that PIE should include infrastructure development through the Ghana Infrastructure Investment Fund (GIIF), which receives at most 25% of annual ABFA. The challenge however is whether or not, after transfers to the GIIF, the remainder of ABFA should be utilized for current expenditure. Various actors have inconsistent understanding about what public investment expenditure entails.

The Public Interest and Accountability Committee (PIAC) interprets public investment expenditure as capital expenditure. For example, in its analysis of ABFA utilization in 2012, PIAC stated that “[c]onsistent with Section 21(4) of the PRMA which requires that a minimum of 70 per cent of the ABFA be used for public investments, 76 per cent of the 2012 ABFA was spent on public investments and the remaining 24 per cent was spent on goods and services…”71

In practise, the Ministry of Finance has consistently disbursed and utilized less than 30% of ABFA to goods and services, implying that 70% or more of the ABFA would be for infrastructure projects. However, available data show that much lower proportion of ABFA received was used by the Ministry of Finance for infrastructure investments in 2014 (41%), 2016 (57%), and 2017 (37%). This is in spite of budgeted expenditure of 30% and 70% of ABFA to be spent on goods and services, and capital expenditure respectively.72

In PIAC’s analysis of the management of petroleum revenues in 2017, PIAC raised concerns that “…only 37% of the utilised ABFA was used for capital expenditure, less than the 70% stipulated in the PRMA.” … “Expenditure as reported by the MoF does not conform to the requirement to spend at least 70% of the ABFA on Capital Expenditure…”. “…the MoF must therefore comply with the provisions of Section 21(4) of Act 815 in respect of public investment expenditure”.73

Thus, from PIAC’s perspective, spending ABFA on goods and services do not constitute public investment expenditure.

Some parliamentarians and representatives of think tanks and civil society organizations (CSOs) have also assumed and adopted the 70:30 ratios as the position of the law for capital expenditure and expenditure on goods and services, such that any other disbursement formula is treated as an infraction of the law. These stakeholders posit that it was the intention of the framers of the PRMA that 70% of ABFA be utilized for infrastructure investments. But a look at the Hansard on the second reading of the Petroleum Revenue Management Bill does not support this assertion. The Joint Committee on Finance and Energy submitted to Parliament that

“…fifty per cent (50%) to seventy per cent (70%) of total petroleum revenue would be used for Budget support each year with the remaining put into savings… [and] that in determining the ratio of Budget support and savings, the Ministry took into consideration the production profile of the Jubilee Field, the country’s infrastructure deficit, and the minimum amount required to replace donor support to the Budget.” 74

The result of the discussions in Parliament is the provision in section 21(4), which is clearly not a complete adoption of the above proposal. The PRMA formula for disbursement of a minimum of 70% ABFA for public investment expenditure provides flexibility to accommodate the intention of the framers to spend more of ABFA on infrastructure, beyond the GIIF. But this is at the discretion of the Minister of Finance. Thus, the Minister of Finance is again clothed with some power to determine what combination of infrastructure, goods, and services would constitute appropriate public expenditure. This has played out in practise.

Table 2: Public investment expenditure decisions in ABFA utilization

| Year | Total ABFA received (Millions GHC) | ABFA utilization for public investment expenditures as percentage of total ABFA received | ABFA utilization in goods and services as percentage of total ABFA received | ABFA utilization in Capital expenditure as percentage of total ABFA received75 |

| 2011 | 261.54 | 100% | – | – |

| 2012 | 516.83 | 100% | 24% | 76% |

| 2013 | 543.78 | 100% | – | – |

| 2014 | 1215.46 | 45% | 5% | 41% |

| 2015 | 1086.29 | 100% | 16% | 84% |

| 2016 | 388.85 | 80% | 23% | 57% |

| 2017 | 733.21 | 45% | 29% | 37% |

Source: Ministry of Finance (2012-2017)

In practice, not all ABFA was utilized for public investment expenditure as the law envisages. But not all of ABFA utilized for public investment expenditure went to infrastructure development. By PIAC’s narrower but strict definition of public investment expenditure as capital expenditure, it would appear that the Minister of Finance failed to comply with the provisions of the PRMA year on year, except in 2012 and 2015.

We, however, posit that except in 2014 and 2017 when less than the prescribed 70% minimum ABFA was utilized, the Minister of Finance complied with both the letter and spirit of the PRMA in spending the bulk of ABFA on capital projects, and the rest on goods and services. In addition to investments in capital projects under the priority areas, 25% of ABFA is transferred each year, beginning 2015, to the Ghana Infrastructure Investment Fund (GIIF). By the end of 2017, the GIIF had received GHC286.3 million, representing 6% of total ABFA from 2011 to 2017.

To strengthen accountability around the use of the ABFA and ensure that public investment expenditures pay off, the two most important discussions that ought to be had in formulating regulations for the PRMA are questions regarding the basis, objective, and outcome of the combination of public investment decisions, as well as demand and supply of information about the basis for programmed but unutilized ABFA.

- Accounting for unutilized ABFA for public investment expenditures.

The lack of public attention to, and absence of an appropriate regulation to flesh out, the fine details of how section 21(4)a of the PRMA operates, has created an accountability loophole, particularly in respect of how ABFA for planned public expenditure remain unutilized. Section 21(4)a of the PRMA states that;

“For any financial year, a minimum of 70% of the Annual Budget Funding Amount shall be used for public investment expenditure consistent with the long-term national development plan and with subsection (3) and (5).”

What this means is that as long as more than 70% of the ABFA is utilized for the stated purpose, the spending requirements of the law have been fulfilled. There are no further requirements for the Minister of Finance to account for the balance of the ABFA where more than 70% but less than 100% of the ABFA has been utilized, except to relinquish such amounts to the Consolidated Fund for further investment with the Banks of Ghana or elsewhere as provided in sections 26 and 49 of the PFM Act 921. This loophole in the law fuels the propensity to intentionally misdirect ABFA from planned public investment purposes to debt financing.

In practise, the Minister of Finance has been unable to account for unutilized ABFA of about GHC1.14 billion, representing about 24% of total ABFA received between 2011 and 2017, despite calls by civil society groups so to do.

Less than 50% of the ABFA was spent on public investment in 2014 and 2017 contrary to the 70% minimum requirement of the PRMA. The balance from 2014 (GHC666.06 million) was reported by the Ministry of Finance to have been swept by the Bank of Ghana.76 Also, the reconciliation reports do not show that the GHC77.7 million and GHC400.9 million worth of unutilized ABFA from 2016 and 2017 respectively were credited to the Petroleum Holding Fund. This is the effect of the combined operation of section 21(4) of the PRMA, and sections 26 and 49 of the Public Financial Management Act. In spite of the mandatory duty the PRMA imposes on the Minister of Finance to publicize all information in the spirit of achieving transparency and accountability in accordance with international best practices, the Minister has failed to explain to Ghanaians why planned ABFA for public investments were unutilized. Also, the penalty for non-disclosure has not been applied despite glaring infractions of the law regarding minimum ABFA utilization.77

- PIAC’s financing and ABFA priority areas

The Public Interest and Accountability Committee (PIAC) is an independent statutory body whose role is to strengthen governance of petroleum revenues by ensuring that the stakeholders responsible for implementing the PRMA comply with the law at all times. Following its establishment in 2011, PIAC struggled to perform its roles due to financing challenges. The Government of Ghana provided some funding to PIAC, but very inadequate and untimely. As a result of civil society advocacy for sustained financing for PIAC, the PRMA was amended in 2015 for PIAC’s budget to be financed from the ABFA.78 By the end of 2017, PIAC had received GHC2,312,078.00 from the ABFA.79

Although PIAC started receiving ABFA support in 2016, there is evidence that the Ministry of Finance is not clear whether or not to consider PIAC a priority area in ABFA utilization. For example, in the 2016 annual report on petroleum funds the MoF stated in Table 11 that of the GHC311,123,056.92 utilized, the priority areas received GHC310,156,056.92 while PIAC received GHC967,000.00. However, in the 2017 reconciliation report on the petroleum funds, PIAC was listed as a fifth priority area to have received ABFA support. The question therefore remains as to whether or not PIAC is indeed a priority area under the PRMA, and if so what the implications are for ABFA investment practices.

In this part of the paper, we attempt to resolve this question using the litmus test for ABFA investments in programmes and activities. The essence is to draw the attention of of legislators and key actors to certain provisions in the PRMA that need further amendment or deeper regulations to make PIAC a stronger accountability institution.

It has already been established that the ABFA is part of the national budget (section 21(1)); that the use of the ABFA must be to maximize economic development, promote equality of opportunity for the wellbeing of Ghanaians, and ensure even and balanced development of the regions(section 21(2)) ; and that the spending of the ABFA within the budget must be in relation to programmes and activities that fall within at most four priority areas selected by the Minister in accordance with the non-exhaustive list in section 21(3). We term this the litmus test for ABFA investment in programmes and activities. To qualify as a priority area for ABFA investment, PIAC must pass the litmus test for ABFA investment programmes and activities.

PIAC is an independent oversight body established by statute. Its members are appointed by the Minister of Finance. Like some state institutions, PIAC is directly accountable to the people of Ghana through Parliament.

The objectives of PIAC are to ensure compliance by state institutions with the PRMA in the management and use of petroleum revenues; provide a platform for citizenry engagement on revenue management and utilization to meet development priorities; and undertake independent assessment of petroleum revenue management. PIAC’s programmes and activities are therefore geared towards good governance practices in the management of petroleum revenues in order to achieve ABFA objectives. PIAC could thus qualify as institution of government concerned with governance whose operations could be strengthened through funding from the ABFA; a priority area listed in section 21(3)j of the PRMA.

Unfortunately, the Committee’s financing from the government of Ghana at the time preceding the PRMA amendment was at the Minister of Finance’s discretion. There is no evidence that PIAC ever received support from the ABFA, although some other government machineries received financing from the ABFA under the capacity building priority area. It is therefore commendable that the PRMA was amended to remove ministerial discretion to provide financing certainty to PIAC from the ABFA for its operations.

By this amendment, however, ABFA support to PIAC does not qualify as a public investment expenditure under the four priority areas selected by the Minister. It is therefore important that the regulation on the PRMA properly defines and separates PIAC’s share of ABFA from other public investment expenditures under the 4 priority areas that ought to be funded with at least 70% of the ABFA. This would give clarity to the limit on priority areas for ABFA utilization.

- The Ghana Stabilization Fund as a consumption smoothing mechanism in times of boom and bust

Revenue volatility constraints from commodity price shocks and petroleum production risks could impact greatly on the Ghanaian economy if measures are not taken to smoothen public investment expenditure of petroleum revenues during bust times. The Ghana Stabilization Fund (GSF) thus receives, invests in qualifying instruments, and saves petroleum revenues to sustain the economy during periods of unanticipated petroleum revenue shortfall.80 There are rules regarding disbursement to, and withdrawals from, the GSF. The GSF receives not less than 70% of excess petroleum revenue, as well as not less than 70% of actual petroleum receipts after disbursements have been made to GNPC and the ABFA.81 Up to 75% of the GSF balance as at the beginning of the fiscal year shall be withdrawn for alleviating shortfalls in actual petroleum revenue.82 By the end of 2017, the Ghana Stabilization Fund (GSF) received $776.55 million from the Petroleum Holding Fund (PHF); accrued net interest of $7.13 million; and closed with a balance of $353.05 million. Of the $430.63 million that was withdrawn from the GSF, $53.69 million was transferred to the ABFA in 2015 to cushion budgetary shortfalls resulting from commodity price dips. This was done in accordance with withdrawal rules under section 12 of the Act.

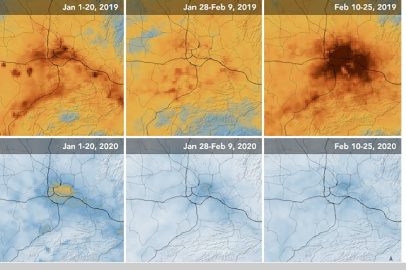

Figure 5: Disbursement architecture of the Ghana Stabilization Fund

Source: Ministry of Finance (2017)

- Ministerial discretion, public debt, and implications for public investment expenditure smoothing

The Minister is clothed with the discretion to cap the GSF, subject to Parliamentary approval, so that petroleum revenues in excess of the capped amount can be transferred to the Contingency Fund for unforeseen expenditure, or to the Sinking Fund for debt repayment.83 In 2014, 2015 and 2016 the cap on the GSF was consistently revised downward without any justification to the public from $250 million to $150 million and $100 million respectively.84 Transfers to the sinking fund for debt repayment constituted $335.76 million, while transfers to the Contingency Fund was $41.19 million.85

The practise of arbitrarily capping the GSF hampers the growth of the Fund and pre-determines the quantum of petroleum revenue to smoothen public expenditure contrary to the rules specified in the Act. This arbitrary capping of the GSF shows why there is the need for regulations for the PRMA. For instance, at a closing book value of $353.05 million as at December 2017, the GSF was capped to $300 million in 2018. Thus, in the context of increasing crude oil prices, the government is unable to save excess revenue for future consumption as these go into debt repayment. The effect is that the government may be forced to incur more debts if the capped amount is inadequate to achieve its purpose of cushioning the economy in times of revenue shortfalls. Furthermore, that the government acquires resource revenues for debt repayment could increase government’s appetite to undertake unsustainable borrowing against the resource revenues. This potentially defeats the fiscal policy principle of fiscal sustainability and maintenance of prudent and sustainable level of public debt as espoused in section 13 of the Public Financial Management Act, 2016 (Act 921). Explicit rules must be defined to guide the Minister of Finance’s capping decision of the GSF.

- Conclusion, key findings, and recommendations.

This paper sought to analyse the loopholes in Ghana’s Petroleum Revenue Management Act (PRMA) as regards the Annual Budget Funding Amount (ABFA) and the Ghana Stabilization Funds (GSF) and juxtapose these against implementation realities to highlight public financial management challenges, if any, and to propose the way forward.

Two key observations were made about ABFA investment for sustainable development:

First, the discretionary powers of the Minister to select priority areas, the absence of an appropriate regulation to guide same, and weak coordination among Ministries, Departments, and Agencies (MDAs) in delivering and monitoring ABFA investments has led to inefficient and ineffective spending that violate value for money goals of the Public Financial Management Act, 2016 (Act 921).

There is the need for the Ministry of Finance to collaborate strongly with local governments, and Ministries, Departments, and Agencies (MDAs) to undertake planned ABFA investments. There is also the need to decentralize funds to cut down on bureaucracies that affect timely release of funds to contractors.

Second, there is the risk of intentional diversion of ABFA for other purposes such as debt repayment and debt servicing. This is because by providing that not less than 70% of ABFA shall be used for public investment expenditure, section 21(4) of the PRMA creates room for ABFA to be unutilized without reasonable grounds. The combined effect of operation of section 21(4) of the PRMA, and sections 26 and 49 of the PFMA is the retention of unutilized ABFA in the Consolidated Fund after lapse of the financial year for further investment with the bank of Ghana or elsewhere. Unutilized ABFA, which were planned for capital investments may be used for other purposes such as debt financing. The Ministry has been unable to account for the reasons ABFA of about GHC1.14 billion, representing about 24% of total ABFA received between 2011 and 2017, was unutilized despite calls by civil society groups so to do.

To strengthen accountability around the use of the ABFA and ensure that public investment expenditures pay off, the two most important discussions that ought to be had in formulating regulations for the PRMA are questions regarding the basis, objective, and outcome of the combination of public investment decisions, as well as demand and supply of information about

the basis for unutilized ABFA in the face of numerous uncompleted infrastructure projects that need financing.

On the management of the Ghana Stabilization Fund (GSF), the Act clothes the Minister with discretion to cap the GSF, and the excess transferred to the Contingency Fund to support unplanned expenditure, and the Sinking Fund for debt servicing. The consequence of arbitrary capping of the GSF to allow for debt repayment is the risk that the GSF may not be adequate to achieve its primary purpose of smoothing public investment expenditure in bust times. It may also increase government’s appetite for more debt. It is important, therefore, that there are well-defined rules a and basis for cap levels over the GSF.

Notes

The following resources, in no particular order, aided the development of this paper.

The United States Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs, Department of Justice Seeks to Recover Over $100 Million Obtained from Corruption in the Nigerian Oil Industry (Justice News 14 July 2017) para 7 < https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/department-justice-seeks-recover-

over-100-million-obtained-corruption-nigerian-oil-industry> accessed 10 June 2018

BudgIT, A Review of Proposed 2017 Budget. < http://yourbudgit.com/wp- content/uploads/2016/12/2017-Publication-BUDGET.pdf > accessed 10 June 2018

Caleb Phillips, Resource Curse in Sierra Leone (Vanderbilt University, 30 September 2013) < https://my.vanderbilt.edu/f13afdevfilm/2013/09/resource-curse-in-sierra-leone-2/> accessed 10

June 2018

Melissa Mittelman, The Resource Curse (Bloomberg, 19 May 2017) https://www.bloomberg.com/quicktake/resource-curse accessed 10 June 2018

Kwesi Amponsah Tawiah PhD and Kwesi Dartey-Baah PhD , The Mining Industry in Ghana: A Blessing or a Curse http://ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol._2_No._12%3B_July_2011/8.pdf> accessed 11th June 2018

Ghana Chamber of Mines, Performance of the Mining Industry in 2012-2016 < https://ghanachamberofmines.org/media-press/our-publications/> accessed 12 June 2018

Mining Revenue Increases to GHC2.16 billion – Chamber of Mines (Ghanaweb, 2 June 2018) < https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/entertainment/Mining-revenue-increases-to- GHC2-16bn-in-2017-Chamber-of-Mines-656968> accessed 12 June 2018

Jim Cust and David Manley, The Natural Resource Charter Decision Chain (Lee Bailey ed, 2nd edn, Natural Resource Governance Institute 2014) 25-32.

Adekola Ganiyul & Okogbule, Eugene E, Relationship between Shell Petroleum Development Company

(SPDC) and Her Host Communities in the Promotion of Community Development in Rivers State, Nigeria: International Education Research Volume 1, Issue 2 (2013), 21-33 ISSN 2291-

5273 E-ISSN 2291-5281

Published by Science and Education Centre of North America

GRA, Domestic Tax Revenue Division < http://www.gra.gov.gh/index.php/divisions/domestic- tax-revenue> assessed 21 June 2018

GRA, Tax Education for all Large Taxpayer Office (LTO) Companies/Taxpayers

<http://www.gra.gov.gh/index.php/category/item/685-tax-education-seminars-for-all-large- taxpayers-office-lto-companies-taxpayers> assessed 21 June 2018.

Ministry of Finance, 2016 Annual Reports on Petroleum Funds https://www.mofep.gov.gh/sites/default/files/reports/petroleum/2016%20Annual%20report%20o n%20the%20Petroleum%20Funds.pdf> accessed 28 June 2018

Ministry of Finance, 2017 Reconciliation Reports on Petroleum Funds https://www.mofep.gov.gh/sites/default/files/reports/petroleum/2017-Petroleum-Annual- Report_2018-03-26.pdf> accessed 28 June 2018.

Ministry of Finance, 2015 Reconciliation Reports on Petroleum Funds Ministry of Finance, 2014 Reconciliation Reports on Petroleum Funds Ministry of Finance, 2013 Reconciliation Reports on Petroleum Funds Ministry of Finance, 2012 Reconciliation Reports on Petroleum Funds

David Aduhene Tanoh, Forum for Allocation from Annual Budget Funding amount held in Accra (Ghana News Agency, 4 Aug 2016) < https://www.newsghana.com.gh/forum-for- allocation-from-the-annual-budget-funding-account-held-in-accra/> accessed 20 July 2018.

UNCTAD (2009). The Role of Public Investment in Social and Economic Development. New York, U.S.A: United Nations

Charlotte J. Lundgren, Alun H. Thomas, and Robert C. York, 2013, “Boom, Bust, or Prosperity? Managing Sub-Saharan Africa’s Natural Resource Wealth.” (Washington D.C: International Monetary Fund). pp 16-17.

International Monetary Fund (2004). Public Investment and Fiscal Policy. < https://www.imf.org/external/np/fad/2004/pifp/eng/pifp.pdf> accessed 10 August 2018

Public Interest and Accountability Committee (2017). 2017 Annual Report on the Management of Petroleum Revenues < http://www.piacghana.org/portal/files/downloads/piac_reports/piac_2017_annual_report.pdf> accessed 9 October 2018.

Official report on parliamentary debate, (4th series, Vol 71, No. 20), published 22 November 2010.

References

1 Petroleum Revenue Management (Amendment) Act, 2015 (Act 893).

2 The United States Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs, Department of Justice Seeks to Recover Over

$100 Million Obtained from Corruption in the Nigerian Oil Industry (Justice News 14 July 2017) para 7 < https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/department-justice-seeks-recover-over-100-million-obtained-corruption-nigerian- oil-industry> accessed 10 June 2018

3 budgIT, A Review of Proposed 2017 Budget. < http://yourbudgit.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/2017- Publication-BUDGET.pdf > accessed 10 June 2018

4 Caleb Phillips, Resource Curse in Sierra Leone (Vanderbilt University, 30 September 2013) < https://my.vanderbilt.edu/f13afdevfilm/2013/09/resource-curse-in-sierra-leone-2/> accessed 10 June 2018 5 Melissa Mittelman, The Resource Curse (Bloomberg, 19 May 2017) https://www.bloomberg.com/quicktake/resource-curse accessed 10 June 2018

6 Kwesi Amponsah Tawiah PhD and Kwesi Dartey-Baah PhD , The Mining Industry in Ghana: A Blessing or a Curse http://ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol._2_No._12%3B_July_2011/8.pdf> accessed 11th June 2018

7 Ghana Chamber of Mines, Performance of the Mining Industry in 2012-2016 < https://ghanachamberofmines.org/media-press/our-publications/> accessed 12 June 2018

8 Mining Revenue Increases to GHC2.16 billion – Chamber of Mines (Ghanaweb, 2 June 2018) < https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/entertainment/Mining-revenue-increases-to-GHC2-16bn-in-2017- Chamber-of-Mines-656968> accessed 12 June 2018

9 Petroleum Revenue Management Act, 2011, Act 815

10 The long title of the Petroleum Revenue Management Act, 2011 (Act 815)

11 Jim Cust and David Manley, The Natural Resource Charter Decision Chain (Lee Bailey ed, 2nd edn, Natural Resource Governance Institute 2014) 25-32.

12 Section 1 of Act 921

13 Based on sections 11, 12, 16 of the PRMA

14 Sections 6 of the PRMA

15 Section 16(1) of Petroleum Revenue Management (Amendment) Act, 2015 (Act 893).

16 Sections 1&2 of Ghana Petroleum Corporation Act, 1983 (PNDC Law 64)

17 Sections 10(1) and 14 of Petroleum (Exploration and Production) Act, 2016 (Act 919)

18 Net CAPI is the difference between the Carried and Participating interest and the equity financing cost.

19 Section 16(3) of the PRMA

20 Section 61 of the PRMA

21 Section 61 of the PRMA

22 Section 11(2) (a) of the amended PRMA

23 Section 11(2) (b) of the amended PRMA

24 Section 21(2) of the Petroleum Revenue Management Act, 2011 (Act 815).

25 Section 11(1) of the PRMA

26 Section 10(2) of the Petroleum Revenue Management (Amendment) Act, 2015 (Act 893).

27 Section 9(2) of the PRMA.

28 Section 11(3) of the Petroleum Revenue Management (Amendment) Act, 2015 (Act 893).

29 Adekola Ganiyul & Okogbule, Eugene E, Relationship between Shell Petroleum Development Company

(SPDC) and Her Host Communities in the Promotion of Community Development in Rivers State, Nigeria: International Education Research Volume 1, Issue 2 (2013), 21-33 ISSN 2291-5273 E-ISSN 2291-5281 Published by Science and Education Centre of North America

30 Section 1 of the Petroleum Revenue Management Act, 2011 (Act 815).

31 Section 3(2) of the Petroleum Revenue Management Act, 2011 (Act 815).

32 Section 3(3) of the Petroleum Revenue Management Act, 2011 (Act 815).

33 Section 3(4) of the Petroleum Revenue Management Act, 2011 (Act 815).

34 GRA, Domestic Tax Revenue Division < http://www.gra.gov.gh/index.php/divisions/domestic-tax-revenue> assessed 21 June 2018

35 GRA, Tax Education for all Large Taxpayer Office (LTO) Companies/Taxpayers <http://www.gra.gov.gh/index.php/category/item/685-tax-education-seminars-for-all-large-taxpayers-office-lto- companies-taxpayers> assessed 21 June 2018.

36 Section 13(2)e of Act 921

37 ibid

38 Sections 3(2) of the Petroleum Revenue Management Act, 2011 (Act 815).

39 Section 4(1) of the Petroleum Revenue Management Act, 2011 (Act 815).

40 Section 2 of the Petroleum Revenue Management Act, 2011 (Act 815).

41 Section 3 of the Public Financial Management Act, 2016(Act 921)

42 Section 10(3) of the Petroleum Revenue Management Act, 2011 (Act 815). 43 Section 10(4) of the Petroleum Revenue Management Act, 2011 (Act 815).

44 Section 60

45 Section 25& 26 of Act 815

46 Section 3 of Act 921

47 Sections 29 & 30 of Act 815

48 Section 46 of Act 815 49 Parliament, the minister, the Bank of Ghana and the Investment Advisory Committee in the performance of their functions under this Act shall take the necessary measures to entrench transparency mechanism and free access by the public to information

50 Ministry of Finance, 2016 Annual Reports on Petroleum Funds (Figure 3 page 19) < https://www.mofep.gov.gh/sites/default/files/reports/petroleum/2016%20Annual%20report%20on%20the%20Pe troleum%20Funds.pdf> accessed 28 June 2018 and Ministry of Finance, 2017 Reconciliation Reports on Petroleum Funds (table 7 page 23) < https://www.mofep.gov.gh/sites/default/files/reports/petroleum/2017-Petroleum- Annual-Report_2018-03-26.pdf> accessed 28 June 2018.

51 Ministry of Finance, 2017 Reconciliation Reports on Petroleum Funds (para 58 page 23) < https://www.mofep.gov.gh/sites/default/files/reports/petroleum/2017-Petroleum-Annual-Report_2018-03- 26.pdf> accessed 28 June 2018.

52 Section 21(2) a, b & c of Act 815

53 Section 21(1) of Act 815

54 Roscoe Pound, Interpretations of Legal History (CUP Arc hive, 1923) 1

55 Section 21(2) d of Act 815

56 Section 21(6) of Act 815 57 Ministry of Finance, 2015 Reconciliation Report on the Petroleum Holding Fund (Government of Ghana 2016) 38

58 Ministry of Finance, The Budget Statement and Economic Government of Ghana for the 2017 Financial Year (Government of Ghana 2017) 48

59 David Aduhene Tanoh, Forum for Allocation from Annual Budget Funding amount held in Accra (Ghana News Agency, 4 Aug 2016) < https://www.newsghana.com.gh/forum-for-allocation-from-the-annual-budget-funding-

account-held-in-accra/> accessed 20 July 2018.

60 Emphasis added

61 Criminal Appeal NO. J3/3/2012(Unreported)

62 Ministry of Finance, 2014 Reconciliation Report on the Petroleum Holding Fund (Government of Ghana 2016) 38

63 Ministry of Finance, 2015 Reconciliation Report on the Petroleum Holding Fund (Government of Ghana 2016)

64 ibid

65 See various PIAC reports and reports by ACEP

66 Section 21(4) of the Petroleum Revenue Management (Amendment) Act, 2015 (Act 893)

67 UNCTAD (2009). The Role of Public Investment in Social and Economic Development. New York, U.S.A: United Nations

68 supra

69 Charlotte J. Lundgren, Alun H. Thomas, and Robert C. York, 2013, “Boom, Bust, or Prosperity? Managing Sub-Saharan Africa’s Natural Resource Wealth.” (Washington D.C: International Monetary Fund). pp 16-17.

70 International Monetary Fund (2004). Public Investment and Fiscal Policy. < https://www.imf.org/external/np/fad/2004/pifp/eng/pifp.pdf> accessed 10 August 2018 71 Paragraph 50 of the 2012 Annual Report on Petroleum Funds 72 See paragraph 73 on page 28 of the 2017 Reconciliation Report on the Petroleum Funds by the Ministry of Finance.

73 Public Interest and Accountability Committee (2017). 2017 Annual Report on the Management of Petroleum Revenues < http://www.piacghana.org/portal/files/downloads/piac_reports/piac_2017_annual_report.pdf> accessed 9 October 2018.

74 See pages 1388-1398 of the official report on parliamentary debate, (4th series, Vol 71, No. 20), published 22 November 2010.

75 The 2015 to 2017 figures include transfers to the Ghana Infrastructure Investment Fund

76 Ministry of Finance (2015). 2015 Reconciliation Report on the Petroleum Holding Funds. Para 47, p. 13

77 Section 50 of the PRMA provides that a person who fails to comply with, or abets non-compliance with, information disclosure requirement under the Act shall be liable on summary conviction to a fine of not more than 250 penalty units.

78 Section 57(3) of the PRMA as amended provides that the budget on the annual programme of the Committee shall be a charge on the ABFA for each financial year. 79 See page 21 of the 2016 Annual Report on the Petroleum Funds, and page 43 of the 2017 Reconciliation Report on the Petroleum Funds.

80 Section 9(2) of the PRMA

81 Section 11 of the PRMA

82 Section 12(6) of the PRMA

83 section 23(3), (4) and (5)

84 See https://ghanaguardian.com/govornment-crippling-stabilisation-fund-ifs

85 2017 Reconciliation Report on the Petroleum Funds.